Click Here for Details

Cork Taint in Wine

©Richard Gawel

....Email this article to a friend....

The waiter reluctantly returns a bottle of opened wine to the kitchen. "The gentleman out there says this wine is corked, and wants another one," he says to the manager. The manager looks at the wine, and grudgingly replies, "What's he on about, there's no bits of cork in there! Give him another one we don't want a scene." I'm sure this scenario is played out daily in restaurants and cafes throughout the world. Such is the lack of understanding surrounding cork taint or corkiness in wine. So what is cork taint?

In practical terms, it is the biggest peril bottled wine buyers face. It strikes sporadically, randomly and often very ferociously. No wine, regardless of its pedigree or price, is immune. What is worse is that it forms in the wine after bottling, and cannot be detected until it is opened. It is the serial killer of wine. So exactly what is it, and how prevalent is it?

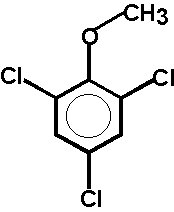

Cork taint is in fact a set of very undesirable aroma and flavour characters that are imparted to bottled wines following contact with their cork. Six chemical compounds have been found to contribute to cork taint. These are guaiacol, geosmin, 2-methylisoborneol (MIB), octen-3-ol and octen-3-one; and the most important of them all 2,4,6 trichloroanisole. TCA as it is affectionately known is a small and chemically simple molecule. With the exception of guaiacol, these compounds are sensorially very potent. TCA can be detected in dry white wine and sparkling wines at levels around two parts per trillion (0.000000000002 grams in a litre of wine), and in red and port wines at around five parts per trillion.

The Chemical Structure of 2,4,6 Trichloroanisole

Such low concentrations are difficult to conceptualise but it is analogous to one teaspoon in a couple of thousand olympic sized swimming pools or one second in 32,000 years. A single gram of pure TCA could badly taint the entire volume of wine produced in Australia each vintage. The other less common contributors to cork taint are not much better having sensory thresholds of around 20 parts per trillion. So how can you tell if a wine is cork tainted?

For particularly badly tainted wines it is relatively easy if you know what to look for. TCA which is implicated in more than 80 per cent of cork tainted wines typically has a musty, mouldy or wet hessian character. MIB and geosmin have an earthy/muddy aroma, guaiacol is smoky or medicinal, and octen-3-ol and octen-3-one smell distinctly of tinned mushrooms.

While most corked wines are musty or mouldy, occasionally one of the other characters predominates. Complex chemical mechanisms underlie the production of TCA. The one of most importance is the conversion of chlorophenols to chloroanisole by common microscopic fungi such as Aspergillus sp. and Pennicilium sp., in the presence of moisture. Chlorophenols have been used as pesticides and as wood preservatives and as such are common environmental pollutants. The uptake of the minutest amounts of chlorophenol by cork tree bark during any stage of its growth, or subsequent manufacture into cork will provide the potential for cork taint production.

Cork bleaching with hyperchlorite (less frequently used now, peroxide bleaching is now favoured), also provide a ready source of chlorophenols for use by these micro-organisms. TCA can also be formed in packing materials and wooden shipping container floors. It can then pass either through the air or by direct contact to previously unaffected corks. For similar reasons TCA is a major contaminant of many other foods and beverages. The exact incidence of cork taint in Australian wines is hotly debated. Estimates range from one to seven per cent. Australian Wine Research Institute records of the incidence of cork taint seen by winemakers in thousands of bottles of wines opened as part of their Advanced Wine Assessment Course suggest that the figure is around five per cent. My experience in running sensory classes for the winemaking degree at the University of Adelaide/Roseworthy Agricultural College over the past decade would suggest a slightly lower rate of around three per cent. Whatever the exact figure, it is indisputable that cork taint is responsible for adversely modifying the sensory properties of a great deal of bottled wine each year. Arguments by even experienced tasters often arise over whether a wine is corked. This is due to a number of reasons. The first is that people vary greatly in their sensitivity to aromas, taints included. A rule of thumb is that for a specific aroma compound, the most perceptive five per cent of the population are about 200 times more sensitive than the bottom five per cent. Therefore when at low levels, you can be sure that not everyone will perceive the taint. Secondly, cork taint manifests itself differently depending on its degree. At low levels, while not being noticed in its own right, the TCA suppresses the wine's aroma and flavour. Under these circumstances, comparison with other bottles is the only way in which the taint can be confidently verified.

The taint compounds themselves also smell differently depending on their concentration. For example, MIB is somewhat earthy at lower concentrations but when present in large amounts has a camphorous aroma. These shifts in the way the taint compounds smell makes them hard to pin down in some wines. Finally to exacerbate these problems of identification, humans quickly become adapted to the musty aroma of TCA. Continued sniffing of a TCA affected wine can result in rapid reductions in its perceived mustiness. In fact TCA is one of the most strongly adaptive compounds known.

The upshot of this is if you think a wine is corked on the first sniff, it probably is. Subsequent sniffing is far less reliable. The question of whether a wine is corked is also complicated by the fact that the same taints can arise not from the cork but from wine storage in TCA-affected oak barrels. Winemakers describe this as musty oak, and typically associate the fault with poorly maintained old oak. However even relatively new barrels can be affected by TCA.

The wine from a single badly contaminated barrel when blended with hundreds of others, will significantly affect the entire blend. Such is the potency of these compounds. So if you open a bottle of corked wine what can you do about it? In short, nothing. Under wine conditions TCA is a very stable compound. After it leaches into the wine shortly after bottling it will remain there outliving the wine itself. No amount of subsequent breathing will clean up the wine. So what can you do? You could take the wine back to where you purchased it. The cork is simply part of the wine's packaging. If its failure results in the wine not being of merchandisable quality then you have the legal right to return it. Large wineries receive hundreds of returned bottles each year on the basis of them being 'off'. Most of these are subsequently found to be cork tainted. Alternatively you could choose to purchase wines with alternative stoppers such as Stelvin capsules or synthetics. However for a range of other reasons, cork is still undeniably the stopper of choice for most consumers and producers, and remains an important component of the wine packaging mix.

To their credit wineries and cork suppliers spend a large portion of QC budgets on identifying tainted batches corks before they are used research into how TCA formation is affected by the growingmaking distribution process continuing. world without TCA? It's must.