Click Here for Details

Volatile Acidity in Wine

©Richard Gawel

....Email this article to a friend....

With all due respect, my long departed father Frank, used to make some pretty awful plonk. A quick jump over our back fence in Marion (what was then one of Adelaide's grape-growing suburbs) to 'borrow' some over-ripe, low acid, bird pecked Muscat Gordo fruit from the neighboring vintner. He would then beat a hasty retreat, never quite knowing, or particularly caring, whether that nearby blast was from the bird scarer or from Mr Scarborough's trusty shotgun. He then eagerly crushed the grapes by hand before open fermenting them in a bucket. Non-interventionist winemaking it is now called. Once the ferment stopped bubbling, he would slosh the so called wine into a few goons (the last of which was always half empty) before storing them in the garden shed to mature.

Each and every flagon of his 'Private Bin' would be considered by the majority of us to be swill. They all reeked of vinegar and a few even had a distinctive smell of nail polish remover thrown in for good measure. They were awful, but were also a great example of one of the most common winemaking faults, volatile acidity or VA. How dear dad went about it was a classic case study on how not to make wine. Even as an amateur.

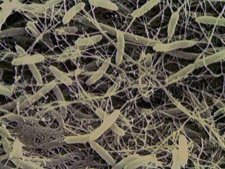

The formation of the vinegary characters were the result of the growth of acetic acid bacteria. There are a number of these, but the most destructive ones in wine are Acetobacter aceti, A. pasteurianus, and to a lesser extent, Gluconobacter oxydans. These bacteria are found on the surfaces of grapes (particularly G. oxydans), and the others are common residents on winery equipment and in used oak barrels. They all have one thing in common. They are aerobic bacteria, needing lots of oxygen to proliferate. They are microscopic single celled critters which have enzymes embedded in their cell walls. These enzymes work to oxidise alcohol into the vinegary smelling acetic acid. Other enzymes also convert alcohol, but this time through a complex set of reactions, into the 'solvent like' compound ethyl acetate. The Wine Aroma Dictionary contains the classic smell of acetic acid type VA.

Acetobacter aceti

In fact, alcohol is the primary energy source for most of the acetic acid bacteria. So where do these bugs get their alcohol from? It can all start in the vineyard. When the grape is damaged by birds or after being infected with moulds such as Botrytis, the juicy parts of the grape are exposed to the air. The grape skin is home to natural populations of yeasts which ferment the exposed juice producing alcohol. The Acetobacter's then use this alcohol to produce acetic acid. When you crush these sorts of grapes, the resultant juice will have a high viable population of Acetobacter, and also a higher than normal level of acetic acid. While the cell counts can be reduced by settling or clarifying the juice prior to fermentation, it is not a particularly good situation to be in if you intend to make a decent wine.

While starting off with healthy undamaged grapes is a good start to making wines with low VA, it is no guarantee. Most acetic infections occur in the winery. The bacteria enjoy living in wines that are both low in acidity and sulfur dioxide (sulfur dioxide is a common anti-microbial agent used in winemaking and it is least effective in low acid wines). But the key ingredient for their growth is oxygen. Oxygen is absorbed by wine every time it is racked (when the clear wine is taken off from the grungy bits that settle to the bottom of tanks and barrels), or transferred between storage containers. Oxygen is also slowly absorbed into the wine through the gaps between the staves in oak barrels. More damaging is when the level of wine in the barrel falls due to evaporation, and this lost wine is not regularly replaced. If not 'topped up' the lost wine will be replaced by air resulting in an ideal environment for acetic acid bacteria to grow. In fact, it is probably true that the most likely time for any wine to become acetic is during its barrel storage, either due to the barrel being ullaged, or its sulfur dioxide levels not being maintained, or both.

Minimising oxygen pick-up combined with ensuring the wine has a good protective level of sulfur dioxide are the two most important winemaking strategies employed to avoid acetic acid build-up in wine. While sounding simple to do, there are some complicating factors. Oxygen is a necessary ingredient in the natural reactions which soften tannins and stabilise the colour of red wines. Wine yeasts also find it difficult to undertake clean and completed ferments if the oxygen levels in the juice are very low. So in many wines, having close to absolute zero dissolved oxygen is not the answer.

Lastly poor bottling practices can also result in acetic wines. Filtration prior to bottling is known to reduce the number of viable acetic acid bacteria. Membrane filtration, in which the wine is passed through a filter which has holes smaller than the acetic acid bacteria themselves, is particularly effective. However once again, if the wine picks up excessive air when it is being bottled then there is a possibility of the wine spoiling after bottling.

So where did Frank go wrong? Almost in every way possible, but I'll let you think about a detailed answer yourself.

Incidentally, like all winemakers, professional or amateur, dad actually thought that his home made and (nearly) home grown Bosko was pretty smart. I didn't have the heart to tell him otherwise.