Polyphenols in Extra Virgin Olive Oil – Measurement and Effects

admin | October 12, 2015This is the second of a short series aimed at explaining the whys, the how and the what (and the what-nots) of analyses that are commonly applied to extra virgin olive oil.

Analysis Name: Total polyphenols

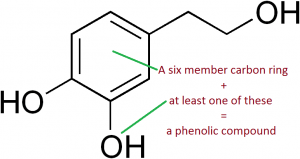

What does it measure?: The combined pool of compounds in olive oil that are in the phenolic chemical group (containing six carbon atoms attached to each other in a ring like formation with one or more oxygen+hydrogen groups attached to the ring). An example of a common olive oil polyphenol is shown in Figure 1. In laymans terms, ‘total polyphenols’ are a measure of the combined total of the most important group of antioxidants in extra virgin olive oil.

Figure 1: Hydroxytyrosol – An example of a phenolic compound found in extra virgin olive oil.

Does the polyphenol level affect extra virgin olive oil status?: No. Many perfectly grown and made olive oils have low or medium polyphenol levels.

How it works: The polyphenols are extracted from the oil into a water/alcohol mix. A reagent is added which reacts with the polyphenols turning it blue/green. The depth of the blue/green colour is measured, and is directly proportional to the amount of polyphenols in the sample.

Is it a measure of quality?: Depends. Quality is a term that encompasses the general concept of ‘fitness for use’. So if you are ‘I want to live forever’ type of person then yes higher polyphenols which are of the antioxidant family could be perceived to be of higher quality in your eyes. But conversely if you want to use extra virgin olive oil to make great tasting grilled potato slices on the BBQ for your hungry kids that don’t taste bitter, then a high polyphenol oil (by a consistently applied ‘fitness for use’ criterion), is of lower quality.

Analysis debuted: 1958. Initially developed for wine polyphenol analysis, It was officially adopted in a modified (but in an incompetely described form) for olive oil by the International Olive Council in 2005.

Unit of Measurement: milligrams/kilogram of oil (1mg=1/1,000 of a gram).

Range in Extra Virgin Olive Oil: 80-2,000 mg/kg (measured as caffeic acid equivalents). Common range 200-400 mg/kg.

Accuracy of method: The first step of the analysis involves extracting the polyphenols out of the oil using a solvent. This step, depending on how carefully it is done, can cause variable end results in the order of +/- 10%. For this reason, it is necessary to repeat the test and take an average.

Use by olive oil producers: Unknown. Probably more so by New World olive producers.

Degree of difficulty: By automated lab standards the method is time and labour intensive, and therefore relatively expensive.

Practical effects of high readings of polyphenols

– Typically more bitter and/or pungent (peppery).

– Greater health benefits.

– Assists in prolonging shelf life.

– Potential for slightly higher smoke point.

Polyphenol level in extra virgin olive oil is affected by:

Cultivar – some varieties of olives tend to produce naturally higher polyphenol levels than others. For example, the average polyphenol levels in oils made from the cultivar ‘Coratina’ are significantly higher than those made from the cultivar ‘Arbequina’.

Olive maturity at harvest – The greener the olives used to make the oil, the higher the polyphenol levels.

Climate – Cool climates tend to favour higher polyphenol levels.

Tree water status – Excessive water availability reduces polyphenol levels.

Enzymes – The use of enzymes as a processing aid increases polyphenol levels

Water use during processing – Adding water to olive paste before extraction (e.g. 3 phase processing) reduces polyphenol levels.

Post harvest – Delays between harvest and processing reduce polyphenol levels.

Disease/Fruit quality – Incidence of fungal disease, olive fly attack and frost damage decreases polyphenol levels.

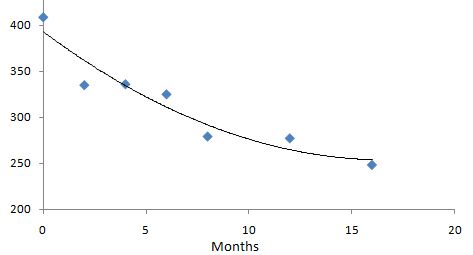

Age of the oil – Polyphenols levels decline as the oil ages.

Other comments:

The method only measures the size of the entire pool of the hundreds of polyphenol types that exist in extra virgin olive oil. Information about the amount of a specific polyphenol can only be achieved using highly sophisticated methods called high performance liquid chromatography or HPLC.

The relatively high cost of conducting the official method has led to an alternative rapid method to be developed. Called NIR or Near Infrared Spectroscopy, it is a method that can almost instantly estimate the polyphenol reading from a drop of oil, and it costs around 1/5 that of the official method. However it has its limitations, and its accuracy is laboratory dependent. Something for another blog post.